Day 2. March 17th, 2020.

Only 1000 words towards WIP MS (work-in-progress manuscript) today but tremendous clarity in terms of the overall story and how it’s all connecting. Progress?

No yoga but a walk around the neighborhood with Jamie. It was nice to see people out and about walking their dogs and waving to one another. I hadn’t been out of the house since Friday. I can’t say it was because of the flu virus going around. It’s not. I relish the opportunity to never leave my abode and I am not an introvert by any means. And I do like to travel. What can I say? It doesn’t add up. But does anything need to add up anymore?

The highlight was listening to educators/ authors/ mentors, Kelly Gallagher and Penny Kittle offer professional development for the second day in a row. Link here. It’s great stuff even if you are not a teacher or even if you are not a teacher with a traditional classroom (because to some extent, we are all teachers). After we listen to them, we go on over to Flip Grid and share updates about our “teaching” thoughts, what we are reading and what we are writing. It’s been amazing to connect with educators who are like-minded, intelligent, and driven to grow. You would think we are all in one school, huh? I wish. It’s hardly the case. And if school was in session for any of us right now, we wouldn’t be connecting like this (maybe at a conference or workshop, if we are lucky).

Anyway, listening to them, made me reflect on many things–teaching seldom leaves time for reflecting (I mean, you try to squeeze it in because it’s essential to good teaching/learning/living but when you are writing in addition to teaching, it can be a real challenge) and I have plenty of time for nothing but reflecting right now.

Once upon a time, whenever I would read a phrase or a passage in a book or an article (fiction and non-fiction) that really spoke to me or one where I was enamored with the language or something that was new for me, I would jot it down in a notebook. Then came blogging and so I would include another’s words in a post. Sometimes I would include my own thoughts and other times, just the passage or quote. And then somehow, in a decade’s time, it all dwindled down to a freakin’ Tweet.

But more honestly, as I balanced writing part time alongside teaching full time, I committed more and more material to memory (because I didn’t stop reading), book-marked places with post-its and underlined passages instead. But there is something about a notebook. Seeing Kelly and other teachers’ notebooks has inspired me to start collecting in a notebook again–for no one but myself, and not my own thoughts but others’ words.

Jamie does this also and has never stopped. So smart.

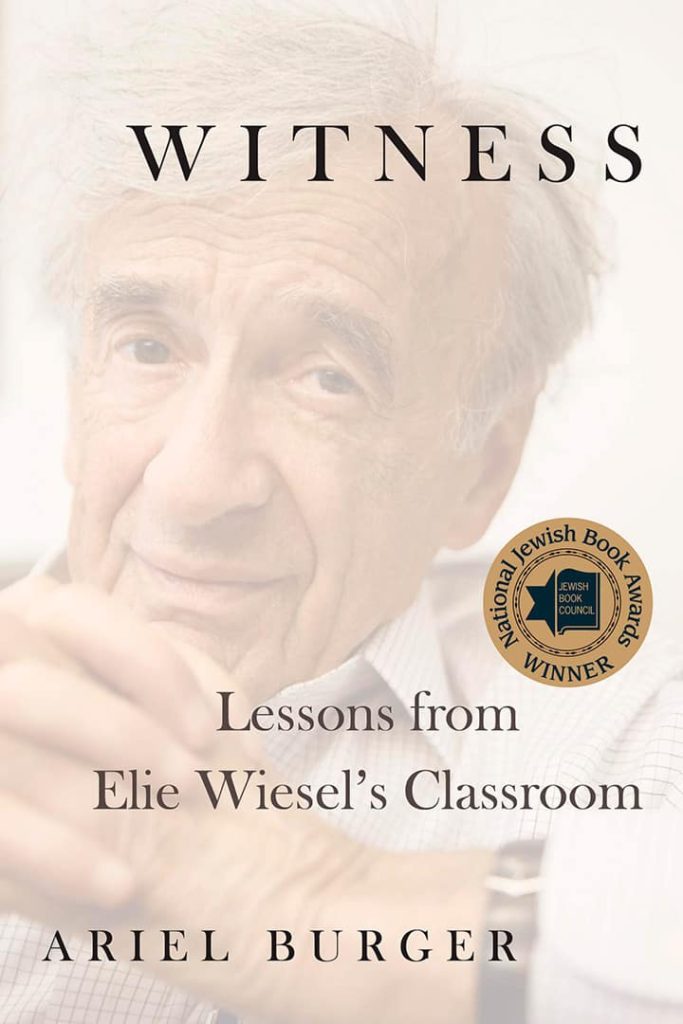

Well, as promised, here is the passage I wanted to share by Ariel Burger from his book Witness: Lessons From Elie Wiesel’s Classroom. If you don’t have this book, you need it now. We can all use it right now.

If I knew you were a teacher and you didn’t have this book, I would get it for you. My friend Lori and I heard Ariel read from this book at the local Jewish Community Center last year. It was a great experience and left a tremendous impression on both of us.

About the book: “In the vein of Tuesdays with Morrie, a devoted protégé and friend of one of the world’s great thinkers takes us into the sacred space of the classroom, showing Holocaust survivor and Nobel Peace Prize recipient Elie Wiesel not only as an extraordinary human being, but as a master teacher.”

I am happy to report that Ariel Burger replied and gave me permission to share this here. I am very grateful. I hope you will be too. Until next time…

The following is an excerpt from Witness: Lessons From Elie Wiesel’s Classroom by Ariel Burger. Used here with permission from the author.

And It Was Enough

One day in class, Annika, a third-year communications major, asks, “How can we, students with comfortable lives, really understand your experiences, much less pass them on to others?”

Because memory is the secret ingredient that creates a morally transformative approach to learning, this question is vital. How does one educate toward memory? How can students become custodians of memories that are not their own?

Professor Wiesel smiles slightly and says, “You are correct that this is thequestion. As we know, it is not simply a matter of information. Our task is to awaken sensitivity to others’ suffering. And this is not a simple task. He continues with a story:

When Rebbe Israel Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism, saw that the Jewish people were threatened by tragedy, he would go to a particular place in the forest where he lit a fire, recited a particular prayer, and the miracle was accomplished, averting the tragedy.

Later, when the Baal Shem Tov’s disciple the Maggid of Mezrich had to intervene with heaven for the same reason, he went to the same place in the forest, where he told the Master of the Universe that while he did not know how to light the fire, he could still recite the prayer, and again, the miracle was accomplished.

Later still, Rebbe Moshe Leib of Sasov, in turn a disciple of the Maggid of Mezrich, went into the forest to save his people. “I do not know how to light the fire,” he said to God, “and I do not know the prayer, but I can find the place and this must be sufficient.” Once again, the miracle was accomplished.

When it was the turn of Rebbe Israel of Rizhyn, the great-grandson of the Maggid of Mezrich who was named after the Baal Shem Tov, to avert the threat, he sat in his armchair, holding his head in his hands, and said to God: “I am unable to light the fire, I do not know the prayer, and I cannot even find the place in the forest. All I can do is tell the story. That must be enough.” And it was enough.

Professor Wiesel lets his gaze travel around the room as he says, “Like the rebbe of Rizhyn, we may not know how to light the fire, we may not know the prayer, and we may not know the place in the forest. Our connection to the past is weak; it may be distant, at a remove. All we can do is tell the story, and we must. But in order to tellthe story, we must first hear the story.”

At the heart of Elie Wiesel’s mission as a teacher was a phrase his students heard him repeat time and again: “Listening to a witness makes you a witness.” Like propaganda, its evil twin, moral education is contagious. And to be effective, it mustbe contagious. Unlike propaganda, though, which tells people what they want to hear or feeds their existing fears, moral education tells people what they need to hear, even when it is painful. “Here is how you can tell the difference between false prophets and true ones,” he explained to the class more than once. “The former comfort, while the latter disturb.”

When moral education works, students investigate and embrace new ways of thinking, learn new habits of questioning, and ultimately, find a deeper sense of common humanity.